Change is the only constant

One of my favourite quotes about life comes from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who proclaimed that “change is the only constant”. While he lived almost 2,500 years ago, those words ring truer than ever in a modern world characterised by seemingly continuous change. This is something our networks are certainly not immune to.

Historically we lived in the same place and had a ready-made network of family and friends that we were born into and stayed in our whole lives. These days, we have more disruptions to our networks due to relocation, job changes and divorce that simply wouldn’t have been possible in previous eras.

The problem is that while we’re experiencing more major life disruptions than any previous generation, we’re not fully aware of the impact they have on our relationships. This means that when they inevitably happen, we’re not fully equipped to deal with them.

Here I explore the impact of six major life events on our relationships by drawing on principles from network science. I’ll also make suggestions as to how you can mitigate their negative side effects to keep your network resilient in the face of these inevitable changes.

We are currently witnessing the highest levels of migration in history. According to the World Migration Report, about 272 million people, or 3.5% of the world’s population is living outside their country of birth as of 2020, compared to 150 million or 2.7% in 2000. This number is projected to increase to a staggering 400 million by 2050.

Plus, with more people in the global north experiencing the freedom to work remotely it’s clear that relocation, either temporarily or permanently, will occure for more and more people. As someone who’s relocated internationally twice—from Boston to Hong Kong in 2008 and Hong Kong to London in 2015—I have experienced this first hand.

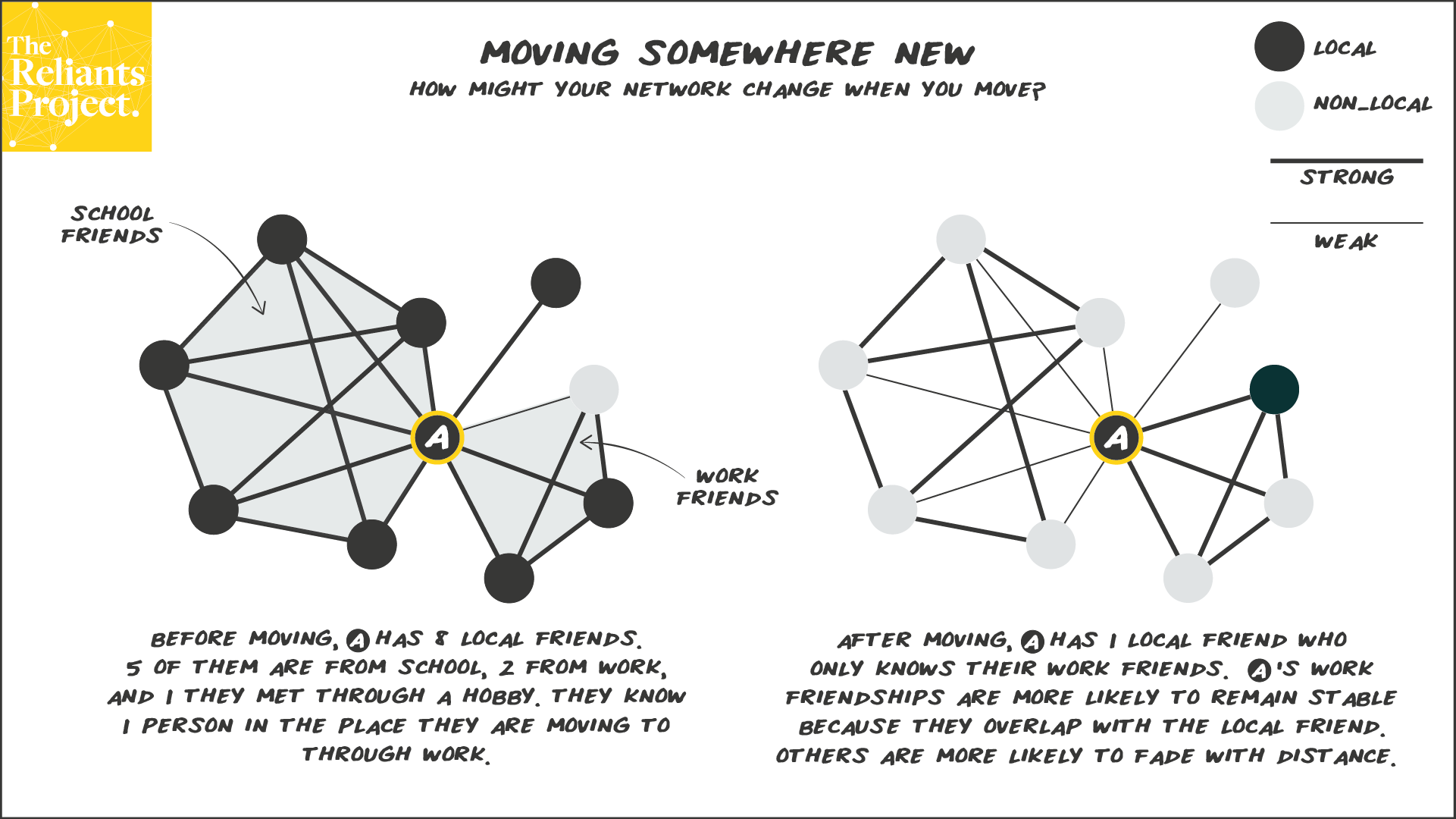

So what impact does this have on someone’s relationships? Inevitably, some friendships from your previous location fade as the lack of overlapping friends and distance begin to take their toll. As shown in the graphic, A’s core network is heavily disrupted by the relocation. They are more likely to maintain their work friendships because they have a local friend embedded in that network, but their ties with school friends are more likely to fade because of the lack of overlap with people their new place.

Maintaining friendships that don’t have ties to your new place is a challenge but with effort they can remain strong. I’m pleased to say I’ve maintained many of my friendships developed in the US and Hong Kong, despite living in London for 5 years now. (I documented my experience building a community when moving to London in this article)

2 | Changing Jobs

The days of staying with a company for decades and retiring are long gone. The average number of jobs in a lifetime is 12, according to a 2019 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) survey. Surprisingly, this data is based primarily on baby boomers. With younger generations more likely to change jobs and even careers than ever before, understanding the impact of these moves on our network is critical, both on an individual and organisational level.

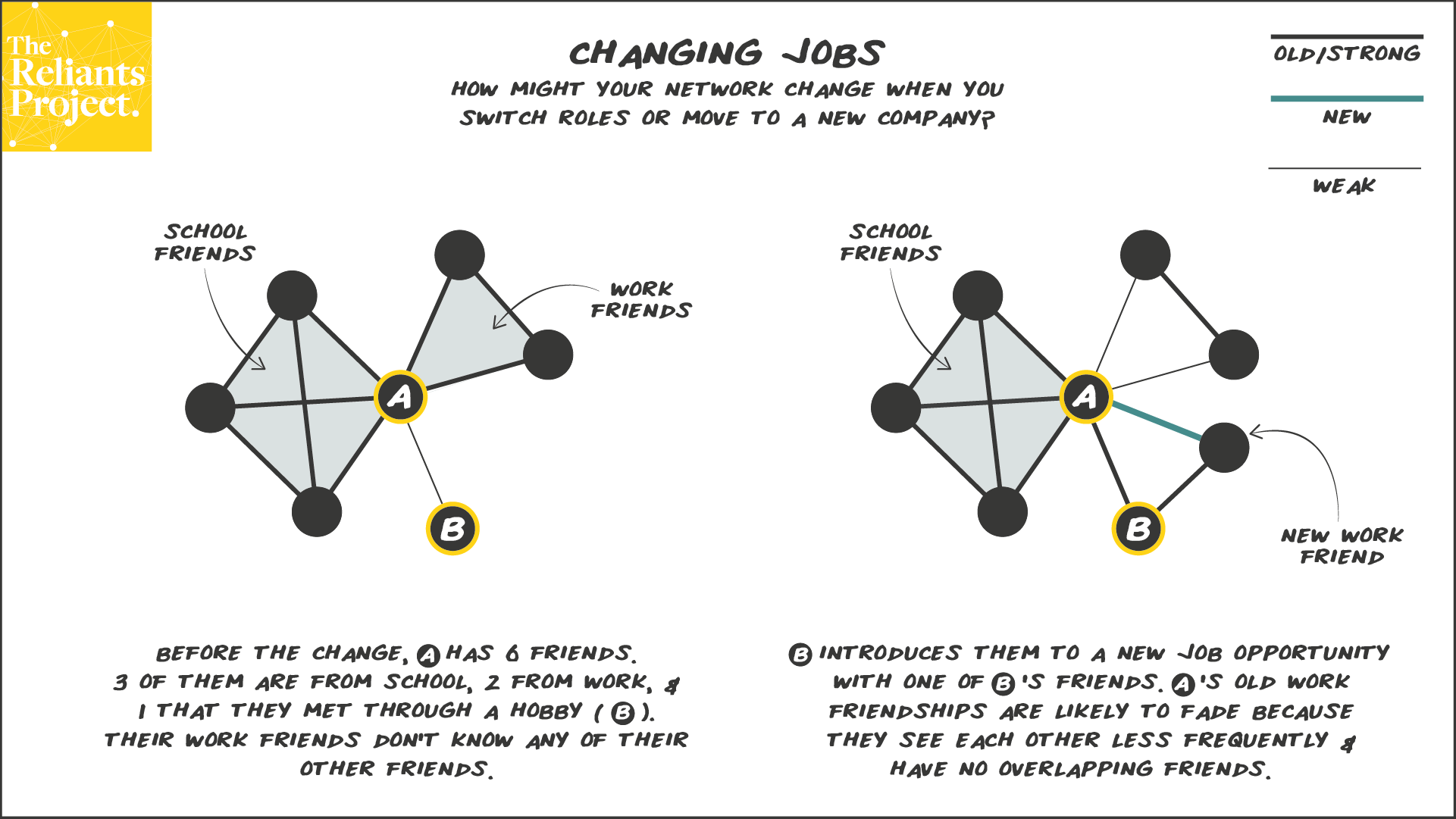

I’ve changed careers 3 times in my life with two of those moves linked to my international relocations. While a job change isn’t as disruptive to your network as a relocation, it can lead to a weakening of ties with former colleagues as the daily time spent together in the office evaporates (see graphic). This effect is also magnified if your work friends don’t know your non-work friends and exist in separate clusters as shown in the diagram.

Michelle Rogan’s work out of Imperial College London Business School, which we discussed on the podcast here, sheds some light on the portability of networks from one organisation to another. The same analysis applies to whether you stay in touch with people from your old job once you leave. The question is whether the relationships or ‘ties’ you have built in your old job organisational or personal?

If they’re personal and you’ve strengthened the relationship by spending time together outside of work, then you’ll be far more likely to stay in touch. But if the only contexts in which you’ve spent time together are related to your job, it’s unlikely these ties will be resilient in the face of this change.

3 | Starting a Relationship

We’ve all had the experience of a friend who suddenly disappears from our network as a romantic relationship becomes more serious. All of a sudden, they’re no longer present at regular gatherings and it becomes impossible to get a slot in their calendar. Chances are you’ve probably been that person yourself in the past.

Research shows that this type of behaviour is natural for both men and women and is simply based on the re-adjustment process that comes from bringing someone new into our inner circle. Robin Dunbar of Oxford University has shown that people typically have five close relationships (what I’d call ‘reliants’) who they would turn to in the most challenging times.

Some of his research builds on this to show that a new partner will push out two of these close friends on average. This means that a person with a serious romantic relationship will only have on average four of these core relationships instead of the typical five, with one of those being the new person who’s come into their life.

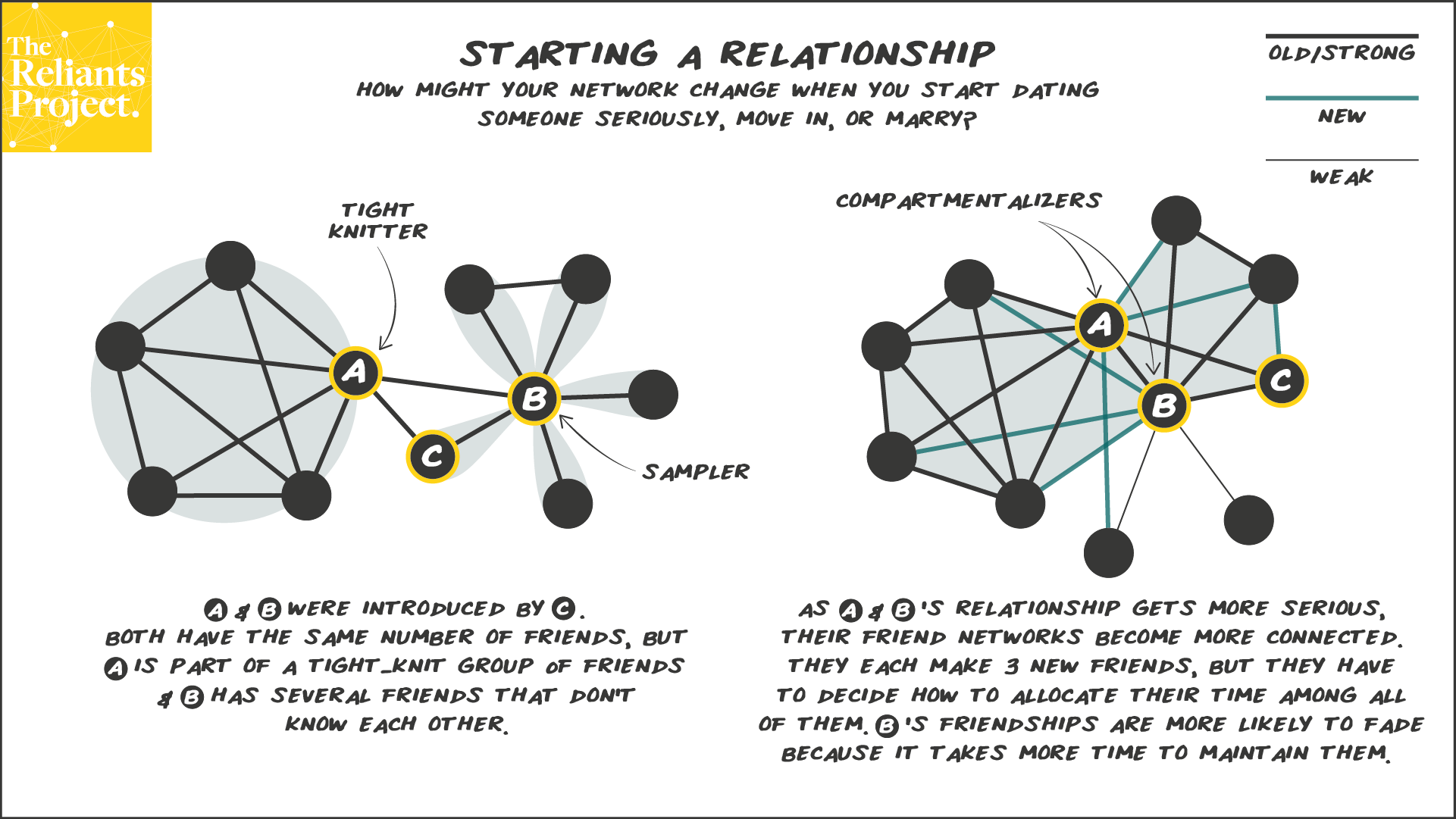

In network terms this presents new benefits as you and your partner’s networks begin to blend. Since meeting my partner in London in 2017, this is exactly what’s happened with both of us building new friendships from the other’s existing network, which I visualised here. This can be a blessing or a curse depending on how compatible both of your networks are. In the graphic, I’ve illustrated a scenario where one partner is a tight knitter whose friends all know each other and the other is a sampler who has several separate relationships with people.

As the relationship becomes more serious and you function more as a unit, both of you begin to operate as compartmentalizers within your shared network. The challenge now becomes how to spend time among all these friends – although this is more of a challenge for B than A. It’s actually more likely that some of B’s ties will fade than A’s because A&B can hang out with A’s tight-knit group of friends together, rather than the multiple times it will take for B’s ties to all be maintained.

4 | Ending a Relationship

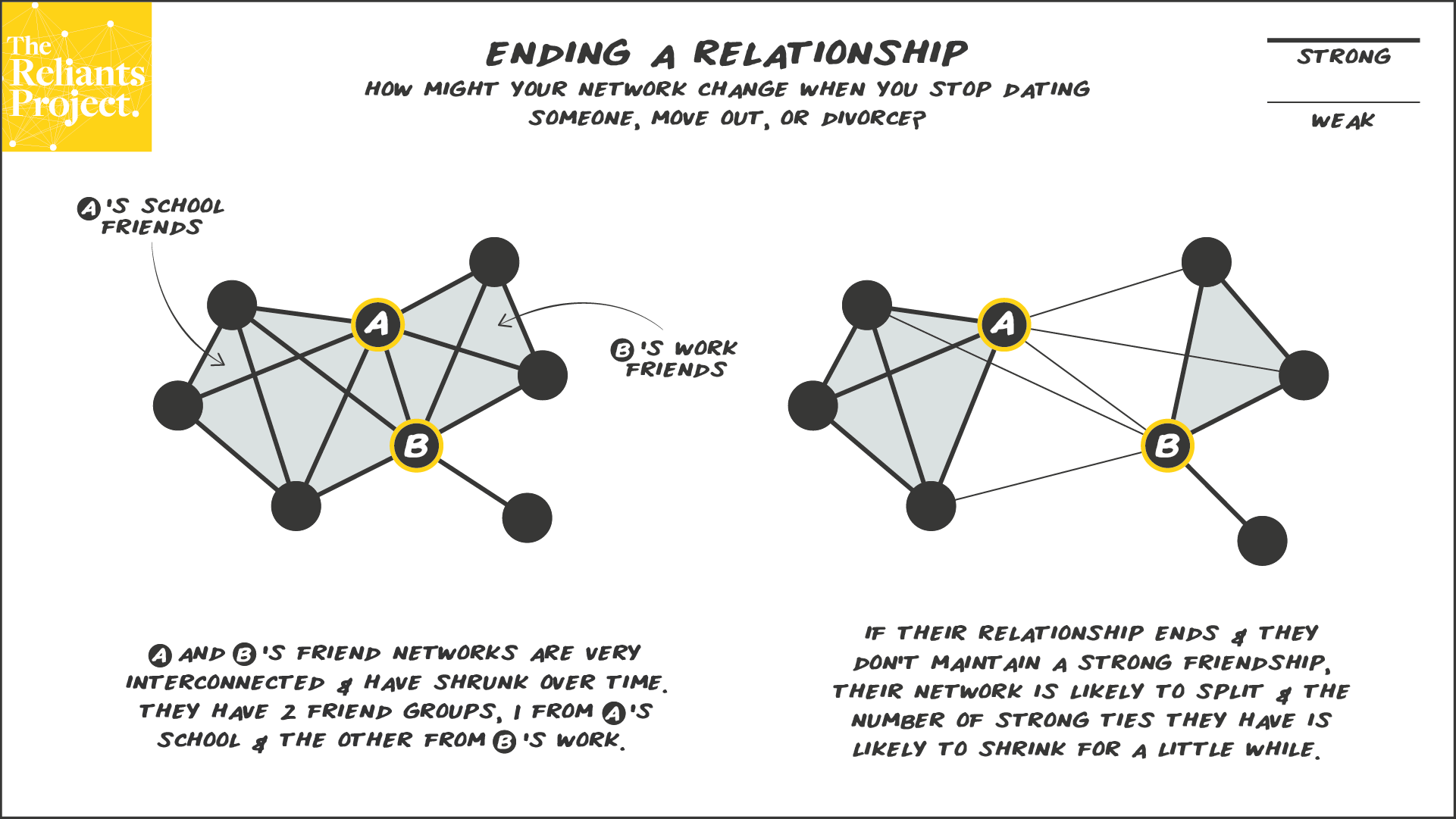

The pain of a serious relationship ending extends far beyond the emotional trauma and the two individuals involved. Assuming the two partners don’t maintain a strong friendship, divorce or breakup means that the shared network they have built together splits off. (I’ve assumed the couple doesn’t have children here to simplify the visual)

The pain of a serious relationship ending extends far beyond the emotional trauma and the two individuals involved. Assuming the two partners don’t maintain a strong friendship, divorce or breakup means that the shared network they have built together splits off. (I’ve assumed the couple doesn’t have children here to simplify the visual)

Research by Geoffrey Greif and Kathleen Holtz Deal out of the University of Maryland documents the shift in relationships that happens when couples divorce. Of the 58 divorced individuals and 123 couples interviewed, almost two-thirds said they had couple friends who divorced or broke up. Over half said that the friendship ended with one person and one in eight said it ended with both.

Naturally, the friends who have a stronger relationship with one partner will be more likely to ‘choose their side’. So A’s school friends stay close to A and distance from B. B’s work friends maintain their relationship with B, while their ties with A fade.

The end of a relationship is also likely to change how you relate to your network in terms of McCabe’s friendship network types, which I discuss here. After my divorce many years ago, my friend network shifted from ‘compartmentalised’ groups of people I usually saw with my husband to a ‘sampler’, with mostly one-to-one friendships. You shouldn’t be going into a serious relationship if you think it’s going to end, but it would be unhelpful to ignore the possibility.

5 | Having Kids

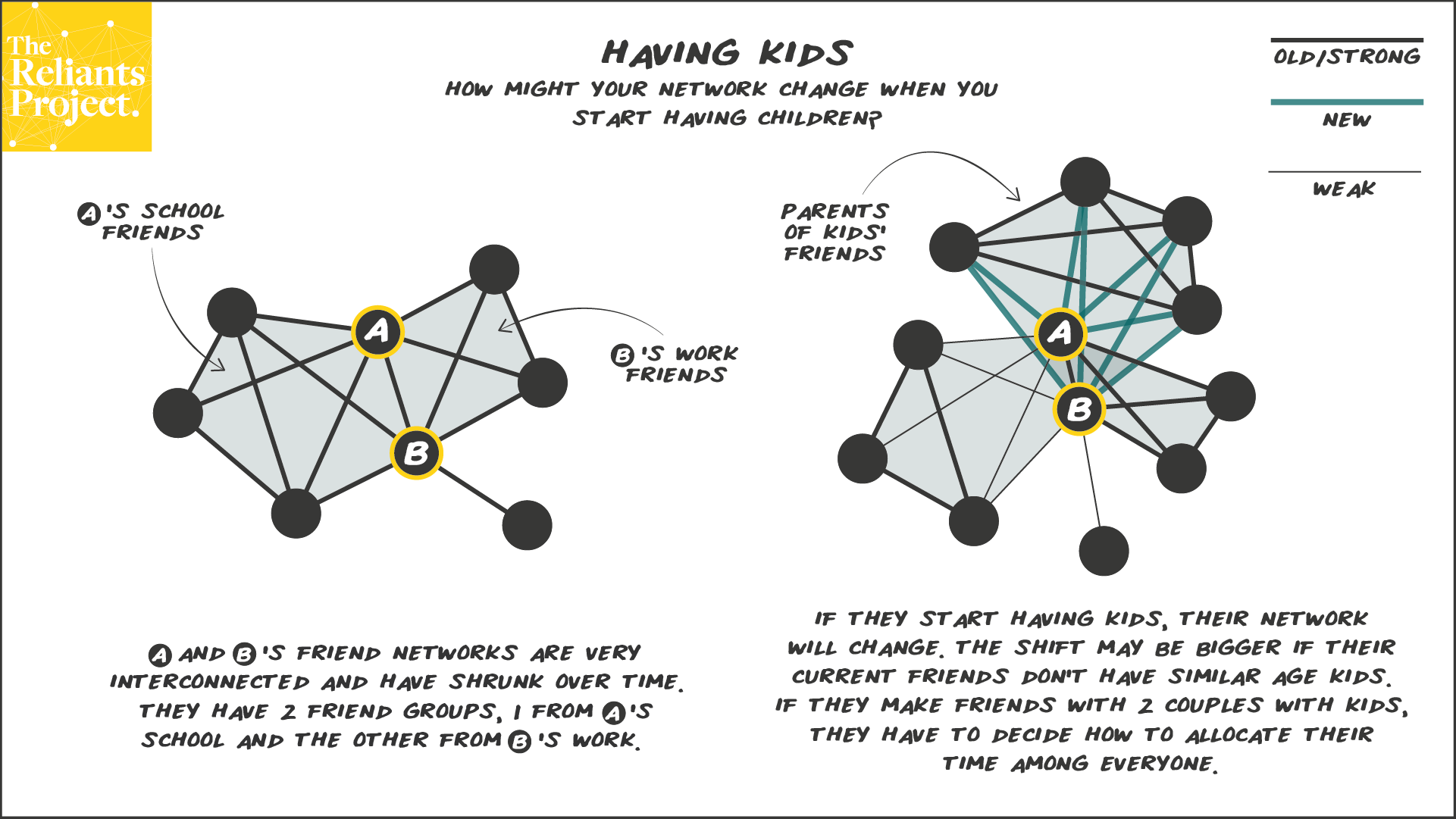

Although birth rates are declining in the global north, the general interest in having children is still high. While it’s something that most couples in serious relationships aspire to, it’s safe to say that the majority of people aren’t fully aware of the impact having children has on their networks beyond the usual platitudes of “say goodbye to your social life”.

According to research, new parents commonly experience a shrinking of their networks and a weakening of the ties with their friends. In a survey of 2,000 parents, the charity Action for Children found that as many as 68% felt “cut off” from friends, colleagues, and family after having children. This may be due to tighter budgets, less energy and an inability to leave the house.

Another study on the impact of parenthood on social networks by researchers from the Netherlands found evidence for the same weakening of network ties for new parents. Tracked over time, the decline seems to hit a trough when children reach the age of 3 at which point the transition back to some semblance of normality begins. Women begin to regain contact with friends once the child turns 5, whereas men were far more likely to remain distant from their former friendships, sometimes even until after the child turns 19.

The same effect that occurs with a new serious relationship is magnified when people have children. Now you don’t just need your partner and your friend’s partner to get along, you also need their children to be of similar ages and get along with yours too! As shown in the graphic below, parenthood will likely lead to the growth of a new network of friends with children of a similar age, if those relationships don’t already exist in your life. This creates yet another force pulling you away from your existing friends, as shown by the weakening of A’s ties with their school friends in the diagram.

For your friends that aren’t in a serious relationship or don’t have children of their own, your newfound parenthood will test your friendship. While you may spend less time together, maintaining those friendships is critical for you to maintain a sense of self outside of your identity as a spouse and parent. This helps to ensure that you have your own network to come back to when you finally come up for air after the first few years of parenthood.

6 | Loved One Passing Away

While life expectancy has been increasing consistently for some time, Benjamin Franklin’s assertion that “nothing is certain, except death and taxes” doesn’t seem likely to change anytime soon.

While life expectancy has been increasing consistently for some time, Benjamin Franklin’s assertion that “nothing is certain, except death and taxes” doesn’t seem likely to change anytime soon.

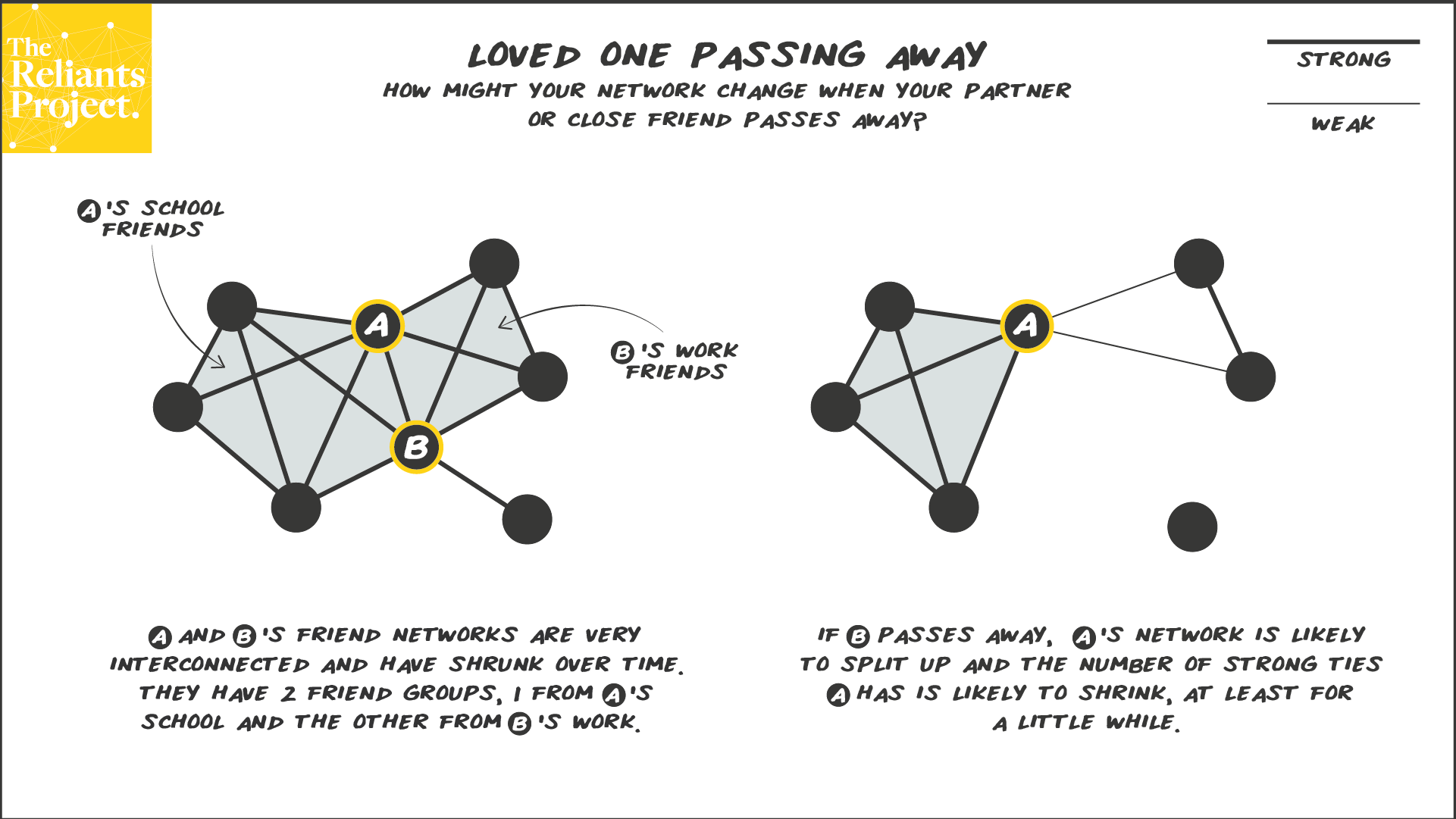

While it may seem morbid, planning for what your life might look like when your partner passes away or helping them think through what life might look like without you is important when you consider the devastating impact death can have on your network. Research even suggests that the death of a spouse can lead to the other partner dying soon after, a process referred to commonly as dying of a broken heart.

As displayed in the graphic below, the death of a partner may lead to the weakening or total loss of ties with their friends. Just as with the end of a serious relationship there is a split in the network that leads to a shrinking that can become permanent without careful cultivation.

Recent research on social networks during crises like the death of a partner have found that friend groups react in three distinct ways:

- Quickly forming temporary bonds that dissolve

- Slowly forming longer-term, in-group bonds

- Dissolving and never healing

Critical to the outcome you’re likely to experience is the strength of relationships you have already cultivated with those closest to you, your ‘reliants’ as I like to call them. These reliants can also help distribute the workload of caring for someone who is in decline, even if these are just small things like keeping you company and lending an ear for a conversation.

How to Avoid Network Breakdown in the Face of Disruptions

While death and taxes are inevitable, the breakdown of your network in the face of life’s inevitable disruptions is not. The accelerated pace of change we’re experiencing in modern life means that you’re bound to experience some disruption. You can manage the downsides if you consistently apply the following three principles to cultivating your own network:

1 | Form Multiplex Ties

Compartmentalising your relationships makes them highly context-dependent and far less resilient in the face of change. A way to address this is to increase the number of dimensions in your relationship: so a friend also becomes a collaborator on your latest passion project or a colleague from work also becomes someone you go hiking with on the weekends. By creating these ‘multiplex ties’ in the parlance of network science (which I discussed with Janice McCabe here) you are making your relationships more durable. Even if one of the contexts in which you interact changes, you still have others to fall back on.

2 | Make Introductions Between People

The other major thing you can do is to introduce the people from the different parts of your life to each other. For example, make an effort to connect your friends from work to your friends from school or to invite your teammates from your local sports team to a get-together with your partner’s friends. This process of bringing others into the fold is an application of the principle of transitivity, which refers to the extent to which the nodes in your network are connected to each other. The more interconnected your network is, the more resilient it will be in the face of disruptions.

3 | Nurture Relationships Yourself

While you may build connections with people through your work, or form friendships with your partner’s friends, you may not necessarily maintain those relationships if the context changes. For example, if you only hang out with your partner’s friends when your partner is around, you probably won’t stay friends after a break-up. That’s why, if you want to retain these ties in the long run, you need to move them towards becoming ‘personal ties’ by nurturing them yourself. The key insight here is that you may not own as much of your network as you think (which I discussed with Michelle Rogan here) and this means you’ll need to put more work in to make sure those relationships are resilient in the long run.

While it may feel like an effort at times, it’s important to apply these principles consistently over time. This is especially when it seems like everything is fine and stable. It’s precisely in those moments that the constant of change reemerges to surprise us again.